My Kyiv Days or How One plus One Became One

Research Diary — I am studying in Ukraine.

— I am studying in Ukraine.

— Is that Russia?

— No, it’s a separate country, next to Russia.

— But they speak Russian?

— Many do, but the official language in Ukrainian.

— Isn’t that the same as Russian?

— Not really…

This was a regular exchange for me, whenever I told my Iranian family and friends about my next stage in life. That was of course long before Ukraine has been imprinted on the global consciousness following its invasion by Putin’s Russia. Back in the 1990s, even for me, Ukraine had only been mentioned in relation to culinary items such as Borscht and Chicken Kiev, or some sports events, notably Sergei Bubka’s pole vault records and the teenager Oksana Baiul’s surprise gold medal at the 1994 Winter Olympics, beating, very deliciously, the self-satisfied-looking Nancy Kerrigan. But Ukraine quickly became a part of my and my family’s life. By the time I left Kyiv, I knew Kiev, as it was still known as, much better than Tehran.

Like Paris, Kyiv is one of those cities with a soul. It also has four distinct seasons, though some years the autumn could be terribly short and quickly blown away by the tides of winter snow. That was the case in 1997. I arrived, accompanied by my parents, on a lovely sunny autumnal day, in October. Months beforehand, I had circled that date in my diary, adding a scribble: ‘Oh God, Is it really possible?’. That was supposed to be my flight to freedom, my one-way ticket to music, to all my dreams.

I had been learning some Russian — those days Russian was spoken just as commonly, if not more so, than Ukrainian, at least in the capital city. So by the time we arrived, I could recognise a few signs and ask simple questions, such as ‘where is the Conservatoire’, ‘how much is this’, ‘thanks’, and ‘please’. I came equipped with a little notebook of useful phrases I had prepared with the help of the BBC — ‘Get by in Russian’ — which my father had bought me at a Tehran book exhibition. I also had plenty of advice from a kind Tadjik lady, Sara, who had been tutoring me for a couple of months prior to my arrival in Ukraine. And so there I was. Lost yet found; excited yet daunted. We took the bus that drove from the Boryspil airport to the city centre. The sun was beaming through the windows as loud Ukrainian pop music was blasting through the radio. ‘How beautiful!’ my mom uttered, referring to the golden leaves outside. I was too nervous to answer. We were heading towards the unknown, and it was all for me and my dream.

A friend of a friend had put us in touch with a former graduate of the Kyiv Conservatoire (National Academy of Music), who in turn had suggested we could rent a room in her friend’s house. What we didn’t realise was how we were about to be conned and taken advantage of by our hosts. They were aware of our total ignorance about the country, prices and geographies, charging us equivalent to their annual salary for a single room in a very dodgy and remote area of the suburbs. We were walking wallets for the locals — it pains me to say that all foreigners were. It was 1997, and although the Soviet Union had collapsed six years back, the old lifestyle was very much present everywhere, from Grastronoms selling items just called produkti (literally products) to suspicion towards anyone not looking or sounding like them.

A wave of the smell of urine and alcohol slapped us in the face as we opened the door to the building where our host’s apartment was. ‘We go back, right now!’, said my mom: a far cry from her usual positive self. ‘We have a beautiful life in Iran; why should you put up with this filth?’ I could see her point. The image of our house in Tehran, designed and built by my father and according to many one of the most beautiful houses in the city passed in front of my eyes. But then I remembered all the tears that I had cried in every room and every corner of that house. ‘We’re here for music’, I said as firmly as I could. ‘Let’s at least give it a try.’ We entered and a new musty smell was added to the cocktail of odours. An old smiling lady welcomed us in. I couldn’t understand a word she was saying. Our intermediary contact, the former graduate, was there. Our common language was French; hers was non-existent, mine was too scholastic. She managed to ask for the money and show us the room we were going to stay in.

Once we were left on our own. My father announced, ‘This is no place for us. I find the next available flight and we go back. We are about to apply for Canadian immigration. Why should you waste your life here?’ I knew he was right. But I also knew I couldn’t face a three-year wait for our immigration to be processed — and who knew, maybe we would be rejected.

I tried to remain as calm as possible, as I turned to my mother, appealing to her sense of logic: ‘You have a choice here; we could go back to Iran. But there is a 100% chance of me dying. Because I will take my own life. You could let me stay here, and there is 50% chance of me dying, because I agree it’s hell. But I am ready to fight for music. The choice is yours.’ My voice was shaking as I held back tears at the sight of my parents — they seemed frail and broken. I had broken them; and I hated myself for that. But I knew they would suffer even more if I returned. ‘It’s time to let me go.’ My dad turned to my mother, exasperated…

— What kind of a choice is this?

— The best one I can give you under the circumstances.

There was a long silence, and I could almost hear my mother’s heart cracking. They had witnessed my suffering for far too long. But to my surprise she answered, defiantly: ‘Then stay, and we help you in any way we can.’

And they did. The following weeks were trying. I had been summoned for an audition for entry to the conservatoire. I had no piano to help me keep up my practice; but even worse, we were moved by our hosts to an even more remote area, outside of the city. Given that we knew nobody and could do nothing, we just followed their orders. They put us all together in a small room in a house with an abusive drunkard man and his poor wife. Our room had no lock, and the drunkard would bang on our glass window at nights. The first cold wave of the year had just arrived, too, with no heating in the room, and unsuitable clothes from Iran. My mother would hold me tight at nights trying to warm me with her body heat. I’d shiver and cry myself to sleep, as she rubbed my fingers trying to bring some blood and heat to them. My wonderful mother… My poor dad would spend all day looking for ads for rentals — I had written on a piece of paper what the word ‘rent’ looks like in Russian. Though mistakenly I had put the word meaning ‘I rent out’ rather than ‘I want to rent’. So, all our phone calls would come back negative, and in the meantime, hosts would charge us big bucks for each phone call. I felt as though a huge block of ice was building inside me, one that would never melt. Everything was dark, cold and painful, above all the pain I was inflicting on my parents.

Then came the audition day. I tried to warm up my fingers, but they were frozen. I arrived in room No. 68, one of the largest rooms of the Conservatoire with two pianos. As I approached the entrance, I noticed a plaque on the wall across the corridor, next to the door of another room, ‘Volodymir Horowitz practised in this room’. Horowitz was one of the reasons I decided to pursue music as a profession, having watched ‘The Last Romantic’, a documentary of his late life in his swanky New York City abode. The plaque gave me a morale boost. I entered my audition room. There were around half a dozen teachers present, as well as the dean (dekan) of foreign students. There were no pleasantries, no greetings. I was shown the piano on the left. I sat and tried to move my fingers. I wasn’t given any warm-up time and my fingers were completely frozen. I had a Bach English Suite and a Schubert Impromptu prepared back in Tehran. I started playing Bach and was interrupted almost immediately. It wasn’t much better with Schubert. I had been praised for that Schubert back home; but now I wasn’t even able to get to the dramatic middle section. The silence was suffocating. I could hear my heart as if it was a ticking bomb to be exploded. All I wanted was to disappear. I remained at the piano, hiding my tears. I could feel the shame and guilt as I realised how hopeless I was. One of the teachers, Mikhail Borisovich (a composer and the then head of composers Union), asked one of his students, who was there to translate for us, to sit and play. She stormed rather violently through a Chopin Etude, while I quietly sobbed. When she finished, she turned to me and mouthed ‘sorry’, realising how dehumanising the experience had been for me. ‘This is the level of our students’, Stepanenko uttered. I felt my face was burning with shame. I was tongue-tied. Some heated discussions ensued between the teachers, and then most of them walked out. One, quite scary-looking, approached me and said, in a broken English ‘I heard music in your playing. You have to work hard and get stronger physically. But I am ready to take you on as my student.’

There it was. The first ray of light and hope, finally. I was in heaven. I felt dizzy with happiness and couldn’t reply. My parents thanked her and embraced me. Suddenly the room felt much lighter… and the cold? Which cold? As I walked out of the Conservatoire, I noticed, for the first time, how beautiful the building shone against the backdrop of the Maidan Nezalezhnosty (Independence Square). I felt I had grown wings.

***

Through the Conservatoire I found an accommodation: a rusty old flat owned by one of the teachers, who happily rented it to me for a much higher price than she should have. Later, and after she threatened to downgrade my marks unless I brought her leather goods from Iran, I left that apartment and moved to cheaper one, owned by a wonderful lady, whom I called Aunt Nelya. She remained my Ukrainian auntie until the last day of my stay, six years later.

Back in the first year, shortly following my audition, my father left for Iran, while my mother stayed for a further couple of weeks to help me settle. It was my birthday and she bought a red beret hat for me, one I still have and treasure. We also bought a 100-dollar, Ukraine-made piano; it did the job, even if every so often I had to dismantle and reassemble it myself.

Then it was time for her to leave. I was to jump from being an over-protected daughter to living independently in an unknown environment. Before leaving, my mother had written all sorts of notes around the apartment: ‘turn off the gas’, ‘lock the door’, ‘there is a hammer under the bed’. The last was in case there was an intruder, though I never worked out how exactly I was supposed to defend myself with it. I took my mother to the airport. We didn’t know that once she had shown her boarding pass, she couldn’t come back to hug me goodbye. She started crying and begging the rigid-looking officer to let her kiss her daughter goodbye. The image of my mother looking at me and saying, ‘I may never see you again’, will forever haunt me. ‘I’ll be all right. I’ll take care of myself. I promise’, I shouted at her over the barriers. And she was gone. Silence fell and I felt a sudden panic. What should I do now?

The first few months were harrowing. In the days before internet, making a phone call back to Iran was no easy task, nor a cheap one. So I could only call my family once a week — the most joyous ritual. I also wrote them letters regularly. What excitement to open my mailbox to see a letter from my grandma, my brother, my father, and above all my mother… And how thrilled I was when I discovered a long blond hair, somehow ending up in the envelope, unbeknownst to her. I cherished those letters with every cell in my body, read them and re-read them in the quiet of my solitary apartment. Up until then I hadn’t really understood what it meant to be completely alone in a crowd. ‘I can’t even tell people I’m cold or I’m hungry’, I told my mother over the phone. ‘Come back. Don’t stay’, was her response. Each time she’d say that, I would get a new breath of confidence and defiance. ‘No, I’ll be OK’. I decided not to tell her any more of my sufferings. Instead, I’d report about my Conservatoire classes. And there was plenty to tell.

The first group class at the Conservatoire that I attended was for musical dictation. Our teacher, Olga Bondarenko, a strict woman but with a heart of gold, started playing a recording of Schubert’s Winterreise, ‘Stranger I arrived…’. I suddenly realised tears were running down my face, and I was unable to stop them. ‘Is it too hard for you?’ the teacher asked anxiously. ‘No, you see’, I replied in my still broken Russian, ‘for the first time in my life, I am in a group where everyone is listening and enjoying music without having to hide from the authorities. I am just utterly happy’.

Kyiv Conservatoire those days didn’t have many non-Ukrainian/Russian students. There was a group of Serbs, mostly bayan players but also pianists and composers. There were also quite a few Korean and Chinese students, almost none of whom could (or maybe would) speak a word of Russian or Ukrainian even by the end of their studies; yet somehow miraculously they would get 5 (the highest mark) in their written and oral exams. There were all sorts of rumours flying around, and given the financial corruption I witnessed at some high levels later, there may have been some truth in them. There were a few other Europeans, including a Greek and a Portuguese both pianists (and the latter a particularly kind and caring person), an Irishman (learning bayan mainly, and enjoying popularity with the girls; he helped me with administrative issues), a Pole, a Croatian. Apart from me, there were only two Iranians. Later there would be many more, but I kept my distance from them. Those days, as now, we were never sure of the political standings of other Iranians, and with my family still in Iran, I couldn’t take any risks.

Since we foreigners were considered slow and probably thick, they had created classes specifically for us, where almost nothing useful was taught. The teachers were mainly those who should have long retired, including one who remembered the Holodomyr, Stalin’s enforced famine of the 1930s. She only gave us three classes before she passed away. Almost every week there was an announcement of a memorial for this or that teacher. Pensions were non-existent, so despite their miserable salaries, teachers would continue working until they dropped dead.

I was thirsty to learn as much as possible. So, I asked if I could attend the classes for Ukrainians alongside those for foreigners. The Dean of foreigners was surprised as she knew the requirements were stricter and more demanding but, she agreed to it. Apart from practising their instruments vigorously, both groups had to study various kinds of history, including history of Russian music (presumably now no longer?), history of Ukrainian music, history of homeland music (in fact Soviet music), and history of world music (i.e. Western classical, but extremely limited). We all also had history of religion (thought by the same teacher who a few years before it was teaching the basics of atheism), philosophy (taught by a Stalinist antisemite who liked Iranians only because of their regime’s stance against Israel), and the history of Ukraine. For Ukrainian piano students there were also classes for harmony and composition, analysis, and the history of pianism and piano pedagogy. The latter was taught by a professor who had created a perfect correlation between the height of the skirts of girls and their marks. I can confirm this was not merely a rumour: I walked into my exam wearing a mini skirt, in the middle of winter. But it worked and I got the top mark, without being asked a single question other than where I was from. It will take me a lifetime to wipe from my memory the disgusting image of the smile on his lecherous drunkard’s face.

They also offered Ukrainian language lessons to foreign students. This almost impossible task was dumped on a most caring lady, called Maria Grigorievna. She was given a cold and windowless room in one of lost corridors of the building, which seemed to have been forgotten by the Conservatoire. The first class had five students only; this soon became just one: me. Her teaching methodology might not have been the most effective, but she was a woman of integrity who had stood up to the tragic fate of losing her husband and son. Another time I had seen her washing dishes in order to make some additional money. Once coming back from a winter visit to Tehran I brought her a wool shawl, that my mother had got her to keep her warm in that freezing room. That was the only time in my life that I saw actual tears of joy. ‘This is too beautiful. I cannot wear this. It’s too good for me.’ It was really nothing special.

The Ukrainian lessons were only for the first year; but I continued to go to her at least once a week, just to see her and keep her company. She taught me Ukrainian folk songs and insisted on correcting my pronunciation of the word sio’hodniy (today) — perhaps the only word in Ukrainian which I can still pronounce accurately! When at the end of my studies I went to bid her farewell, she showed that she had kept the shawl in the original packaging that I had brought her six years earlier. ‘But you should have been wearing this’, I said astonished. ‘But I get so much pleasure from taking it out and looking at it and thinking how kind your mother has been.’

Outside of the Conservatoire I exposed myself to as much music as I possibly could. The Kyiv Philharmonia was just 15 minutes’ walk away, as was the opera. There were also regular concerts at the main Catholic church of the city, which was a few minutes’ walk from my rental apartment. I attended as many concerts as I could; and almost always for free. One of the Conservatoire students once told me that music was our job, and we shouldn’t be expected to pay to work. This stayed with me, encouraging me to employ the most outrageously creative solutions not only to sneak into concerts but also to find the best seat possible. I wonder what has become of those ushers, who after a while started suspecting that something was not quite right. At the same time, I was much more friendly with them than any of those seated in the expensive VIP seats. A few years later, when I had become a cultural correspondent for what was then one of only two English-language periodicals, I would get press invitations. But I secretly missed the adrenalin rush of being a stowaway, hiding under the stairs during the pre-concert warm-ups and then trusting my instinct to pick a VIP seat that I felt most likely to remain unclaimed. In this way I saw Penderecki conduct his Credo, Kremer play Schnittke’s Concerto Grosso, Silvestrov attend his Metamusic Symphony, Montserrat Caballé, Yuri Bashmet, et al.

There were many encounters within and beyond the Conservatoire that I shall never forget: ones that helped me get through loneliness, cold, homesickness, marginalisation, and my own demon, depression. It was seeing the courage and dignity of those oppressed individuals that gave me courage to continue and fight. Kyiv is full of pain. Sadness is a part of the culture. A friend and specialist of Ukrainian folk music once told me, I think only half-jokingly: ‘Ukrainian happy and sad songs all sound the same — sad. The difference is the sad ones start with “Oy”, whereas the happy ones start with “Ai”.’ The greatest pain I witnessed was the ever-growing gap between the poor and the wealthy.

My apartment was close to a modern entertainment venue called ‘Palats Ukraina’ (Palace of Ukraine). It was the venue for starry events, whose tickets would usually be equal to a Conservatoire teacher’s annual salary, if not more. These were often concerts by stars who were too old to perform properly elsewhere but were still able to get cash by virtues of names, especially from the Nouveaux-riche of Kyiv. Limousines would stop on the main road, once called ‘Red Army’, and huge men in leather jackets would get out, followed by long legs attached to often a blond, highly made-up young woman, wearing a fur coat even if it wasn’t cold. A few metres away and a few steps down was the underground passage leading to the metro stop. In the evenings, there were elderly men and women standing by the walls, with some knickknacks, bread, a few rotten apples, or just a begging bowl with an icon.

I came out of the metro one cold winter night, knowing a big concert had been on, and wondering if I should cross to the other side to avoid the limousines waiting to take their VIP passengers home. A shaky old voice shouted at me something in a very thick accent. I looked around and I saw a very old woman. She was wearing a black, wool scarf and slowly stepping on the spot to keep herself warm. It was minus-25 that night; probably even colder in the corridor, as there was a sharp wind. ‘Come and buy this bread’. She was still hard to understand, but seeing she was pointing to the loaf of bread in front of her, I worked out what she was asking. ‘I don’t need this much bread’, I answered. ‘Come and buy it. It’s fresh’ — it certainly didn’t look fresh. I smiled and shook my head as I tried to walk quickly past. ‘Come and buy. I am cold and want to go home. I have to sell this before I can.’ It strangely resonated with the Little Matchstick Girl story, except that this wasn’t a story, and she was no little girl. She was at least 70, and her face and body told of all the cruelties of her fate. ‘I’ll give you money. But sell your bread to someone who needs it. This way you’ll have more money’, I answered. ‘I can’t accept money. I am not a beggar’, she said. I gave in and bought the bread. She gave me the change, even though I insisted I didn’t need it. She then went on telling me how she tried to finance her grandson’s education. As with many, her son had fallen to the evil of alcohol. This was a familiar story and one that my own landlady had to endure.

At this point I noticed her gloves had huge holes and her fingers were visibly blue with cold. I took out my gloves and gave them to her. ‘Take these. I live about 15-minutes’ walk from here. I can survive’. Her large blue eyes looked at me with the utmost gratitude, as she tried my gloves on. ‘I don’t have any more bread to give you in exchange.’ ‘It’s a present. No need for bread’, I answered. From that evening on, every time I took that metro stop at a late hour when she was there, she would give me, forcefully, a loaf of bread without taking any money for it. I’d stop there and talk to her for a while and keep her company… until she stopped showing up, and I knew I had lost a friend to the cold night.

***

Kyiv was my making. It was also my breaking. I left after six years, with more wounds than when I arrived. I knew I had to close a chapter for ever, leaving behind those I loved and cared for. But my wounds had another source too: the beautiful city was also home to much marginalisation, racism and psychological abuse. As an Iranian, I was repeatedly subjected to stereotyping regarding ‘oriental’ women and of course Muslims. I gradually found out that unless I denied my identity as an Iranian, I may be able to fit in. So, within the Conservatoire I cut links with other Iranians and only befriended ‘local’ people. I negated everything that had to do with my heritage and culture and fully immersed myself in the Ukrainian lifestyle, adopting even their superstitions.

Within the Conservatoire, this was helped by the Russian-sounding name I was given. My Persian first name was curiously similar to a Russian name, derived from a novella by Turgenev, Assya. And that became my new Ukrainian name: Assinka or even Assichka in the endearment forms. And I loved that name. Assichka was as sweet and innocent as her name. Most of my Ukrainian friendships, even within the Conservatoire, however, were thanks to my unusually good knowledge of English. Ukrainian students were obliged to study English as a part of the curriculum, and almost all of them struggled with it. I couldn’t blame them. The methods and books were criminally old-fashioned and Soviet-styled. Their coursework was entirely about translating from one language to another: not useful phrases but absolutely nonsense and badly-written long texts about the history of the Conservatoire. I offered free English lessons… free, well, the price was really friendship. Other times, it was a simple quid pro quo. When I had do coursework for my Philosophy module, one of my informal pupils was on hand to help proofread my text; when my piano teacher vanished for almost a year, another such friend would occasionally tutor me.

Outside the Conservatoire, my transformations were even more drastic, as I developed an alter ego, which gradually took over my own identity. It all started with an advertisement for teaching English. I contacted the Institute in question and introduced myself with my Persian name. I explained I had studied English at University and had experience of teaching. I was rejected on the spot. I called back a bit later. I introduced myself, in English, as Michelle. ‘Oh, Michelle, ma belle! What a beautiful name!’, the lady on the other side replied. ‘Where are you from?’, the question most often asked of any foreigner. ‘I am half English’, I lied, remembering a schoolmate in Iran, who always claimed her mother was English, knowing nobody could ever check that in her documents. ‘Wonderful. We’d love to have you as our teacher.’ I had also changed my look, dying my black hair light brown, and applying whitening skin products on daily basis. And so when I met the head of the Institute, I was immediately accepted without showing any documentation or proof of experience.

That was the beginning of a double life. Outside of the Conservatoire I was the bubbly, full-of-life Michelle (crazy little Michelle as one of my language pupils used to call me), a successful and highly in-demand English teacher, loved by whomever knew her. Within the Conservatoire, I was the long-suffering, sweet but frail Assya/Assia, thirsty for love and attention.

As Assia, having people pity me was my main weapon to survive the emotional and psychological turmoil, especially from some of the teachers. My greatest chagrin came from my specialism teacher, who by taking me on had become, in my mind, a mother figure for me: this despite her cold and forbidding nature. My naïve sense of unconditional love was tested daily by remarks such as ‘you are like a dog, who instead of talking just barks’, in reaction to my playing. These gems were complemented by my chamber ensemble teacher (who happened to be the niece of Boris Lyatoshinsky a foremost Ukrainian composer of Soviet times): ‘you are like a ballerina who has one leg shorter than the other. Someone like that can never be a ballerina, just as you can never be a pianist.’ Each remark was a dagger… I would cry, try to heal, and return, only to hear more about being ‘superfluous’ and ‘a burden’. There were no mental health or complaint resources available at that time, except for some kinder spirits, such as my accompaniment teacher, Natalia Petrovna Kozina, who continually and persistently defended me against these attacks and offered me the love and support I craved. I used to run to her class and ask if I could just sit there and cry.

Natalia Petrovna was also the first to plant the idea of an academic future in my mind, noticing my curiosity for the music I was playing, beyond notes and technique, and for my interest in unorthodox repertoire, despite or because of the fact that all one could hear from practice rooms were the same competition-style standards. She was instrumental in my decision to attend theory classes and eventually pursue an additional specialism in Music and Arts Criticism, alongside my piano studies. I knew I had access to a rich library, and I wanted to use it as much as I could. This was especially the case when choosing my repertoire. I would go through the library catalogue (all cards then, of course) and pick the most obscure scores and ask the librarians to hand them to me, only to return then after a few hours of going through them at the piano. They certainly didn’t appreciate my research instinct. Years later when I made a return visit to Kyiv, I was apprehensive that they might still remember me. And they did: ‘You’re the one who used to order all those strange scores!’ said one librarian, pointing to me with a smile. ‘Yes, that’s right. I’ve ended up doing a PhD at the Sorbonne, though!’. They were surely impressed. On the same trip I so wanted to go to my chamber ensemble teacher, the one responsible for the ballerina remark, to show her how utterly wrong she was; but I was told she had passed away. I waited for a few minutes outside room 68, knowing my speciality piano teacher was there. But again, I couldn’t summon the courage to knock on the door. I knew she would still find a way to hurt me. I had closed that chapter.

For the first three years of my studies, I would fly back to Tehran during winter and summer breaks, to see my family and relatives. These were wonderful visits. Everyone was curious to know what my life, or indeed any life outside of Iran was like. I would hardly get any time alone, as the famous Iranian hospitality would mean that every day I was invited to one relative’s home. Then in 1999 we finally received our immigrant visa for Canada. We were obliged to ‘land’ in Canada within a certain time limit. So, in December 1999 we flew from Tehran to Montreal where we became ‘landed’ immigrants. I returned to Kyiv with a new sense of confidence, as if I had been given a plan B, that I could fall back on if the pain became too much; but I never did, not until completing my studies. That summer was the last time I went to Iran, although I didn’t know it at the time. Parting from my grandmother, whom I loved dearly (deep love for and trust in one’s maternal grandma is very much a part of being Iranian). I promised I’d come back to see her. But I never did. She gave me a parting gift, that has accompanied me to this day, a Quran with a note from her in it: ‘Assa jan. You have lived through so much in your short life. You are a real lioness. I hope one day you will write the story of your life.’ This Quran has accompanied me to every corner of the world, and still carries my grandma’s note.

Because of the huge expenses of immigration process, I realised I needed to support myself financially in order to reduce the burden on my parents. Additionally, the National Bank of Ukraine, where I had put my money, had gone bankrupt, making me lose all my money and saving. I’d only get a fraction of my money several years later. So I expanded my English teaching (Michelle’s territory), and to that added a job as a cultural correspondent for What’s on, Kyiv, one of the few English journals in Kyiv for expats. At ‘on, I also started the process of integration of my two personae. They knew I was Iranian (although by then I was also almost Canadian, officially, which I used as a justification for employing me for an English-speaking job). And I took on the name Michelle Assia and later Michelle Assay for my writings (at the risk of mis-pronunciation — it’s Assay as in the Italian allegro assai). Thanks to What’s on, I no longer needed to sneak into concerts and operas; I was invited to them. I had to explain this to my usher ‘friends’, who were still looking out for me.

— Don’t sit here. I know there is an invitation written for this seat tonight.

— I know! It was for me.

— How on earth did you get hold of that?

It was almost a Cinderella-like feeling. But I was in too many ways like Cinderella. The additional work meant that I needed to find a way to fit in my piano practice. This meant arriving at the Conservatoire around 6 a.m. as the cleaners entered, and finding a piano practice room for three hours, before the first classes at 9.00; then classes, followed by either teaching English at home or going to concerts/festivals and finally passing by the What’s On office to write up my report. This took a toll on my health, and after a few months, my body gave up. I had one illness after another, until finally shingles put a stop to everything. I was forcefully transferred to a public hospital – for some reason they considered shingles deadly dangerous and infectious. There I came face to face with death; not because of shingles but because of the abysmal state of hygiene and care. In delirium and agony, I started writing my farewells, as I was stared at by a crow (Schubert Winterreise was again my life soundtrack), my only daily visitor, from the curtainless window of the room.

Once returned to the real world, at What’s On I face another end to my Cinderella-story. As Westernisation and corruption among rich expats and nouveaux riches grew, What’s on gradually turned into a magazine for exclusively popular culture, collaborating with a controversial model agency, which years later was in the news for the abuse of under-age girls. I regularly saw some of these two-metre girls in the offices of What’s on. Soon my pieces felt incongruous to the journal. Imagine a girl in a sexy pose on the cover with a headline of a new hedonist club opening in Kyiv, and then turn to a whole-page coverage of a Choir festival in Ukrainian major churches. The day I dreaded arrived, and I was summoned by the editor — a young Brit, who gave the impression of a young man with a lot of toys (girls) than a chief editor. I had prepared a whole speech about the fact that no other English source within or outside of Kyiv reports on these major events, and how we would be unique. He would have none of it. He excused the funding and the fact it had to all go towards popular culture and fashion. I was paid about 100 dollars a month, so I couldn’t believe that money could have been the real matter. I suggested I could work as a volunteer, and I did for a short while, mainly writing on cinema and theatre and only if starry troupes were in town. But eventually they decided more money could be made from selling my inches of the journal to an advertisement for a club or modelling agency. I felt like I had lost a family.

At the Conservatoire, too, my main teacher was growing increasingly hostile towards me. She had left all her pupils without a teacher for almost a year while working for a much higher salary in South Korea. During this time, her Ukrainian students turned back to their college teachers. I was left with nobody to teach me. So I persisted in getting some supervision from other teachers, especially given that, unlike Ukrainian students, I was paying for my education. When upon her return she heard about this, she accused me of being ‘demanding’. I could feel that resentment towards me was building up in her, which was heart-breaking for me, having considered her my Ukrainian mother.

Through all this, music was my refuge. I would walk in the beautiful streets of Kyiv listening to Mahler’s Sixth Symphony on a Sony Discman, feeling the whole of nature suddenly moving to the rhythm of the music. There was also Skryabin’s music, which I had discovered in my third year of studies, alongside paintings of the Himalayas by Nikolai Roerich. By the fourth year, however, I had fallen in love with the music of Shostakovich, having heard and been haunted by his 14th Symphony during a history class. The walls of my apartment were covered with photos of Shostakovich. My love for Shostakovich would shape the rest of my life in ways I couldn’t have imagined.

And so came the final year of my studies and the dreaded Gost (State) Exams. By this time, as a result of continued belittling from my main teacher and my Chamber ensemble teacher, I actually believed that I was never going to make it. It was my accompaniment teacher, Natalia Petrovna who had become my emotional and educational supporter. She rightly advised me to choose my repertoire strategically in order to showcase what she called my intelligence and musicality rather than technique. There were three full programmes to be prepared for the final exams: one for accompaniment, one for chamber ensemble and one hour-long one for the ‘specialism’ (solo piano and concerto). For my concerto I chose Honegger’s Concertino: partly to avoid the competition with exponents of the standard competition-warhorses, partly because — subconsciously — I was on my way towards being a researcher-performer. The Concertmaster diploma also required a separate exam of score reduction and singing of an orchestral/choral scene. Again, Natalia Petrovna smartly advised me to sing in a language other than Russian or Ukrainian. I chose a scene from Lalo’s Le roi d’Ys in French. For the concert element of the accompaniment, I included a work by an Iranian composer (Morteza Hannaneh), which proved very popular with the jury. For the chamber ensemble exam, my teacher, who had systematically humiliated me throughout the past five years, decided none of the Conservatoire ensemble had any time for me. ‘You are just not worth their time.’ I felt again like Cinderella being forced to give up on the ball. I didn’t give up and managed to find my own prince, the husband of a friend, a flautist who kindly agreed to play Poulenc’s Flute Sonata with me. The most challenging of the exams, however, was the main specialism (piano solo). The repertoire was the standard polyphony, Viennese classical, Romantic, concerto, and 20th century, all in all lasting one hour. After some frustratingly humiliating and austere discussions with my teacher, we chose the programme, only for her to insist on changing the polyphony component less than a month before my actual recital. I often wonder if it was a deliberate act of sabotage. But back then I’d have trusted my life to her, so I agreed and launched myself into eight-hour-long practice routines, to learn a brand new polyphonic piece, Honneger’s BACH, well enough to play at my final recital. Naturally, it was never going to be settled and properly matured.

Alongside all these, we had to complete a dissertation for the pedagogy component of our qualification. This was as well as holding an open lesson, for which I brought in the daughter of a friend (poor thing), and passing exams on various theoretical courses. Having by then fallen in love with theatre and started reading Stanislavsky’s books, such as An Actor Prepares, I decided to focus on appropriation of theatrical methods, such as Stanislavsky’s and Meyerhold’s Biomechanics, in piano pedagogy. I found the hours spent on the project some of the most exciting and invigorating moments of my life at the Conservatoire. I also had to create a portfolio of my music journalism for my music criticism speciality. This included my previous work but also covered the latest Horowitz piano competition.

Finally, the day of the Gost exam was there. I had volunteered to go first. I didn’t have any parents to wait for, and frankly I just wanted the whole thing to be over. It was a sunny early summer day, and even at 9 a.m. the Small Hall of the Conservatoire was pulsing with heat and humidity. All the windows were open; but instead of air we had lots of pukh(fluff)) coming in. As I started playing, I could hear people entering and banging the door, noisily unwrapping candies and crinkling their plastic bags (a staple of Ukrainian ‘fashion’ at that time). These were members of my jury, and I had been warned that there would be a lot of interruption on purpose, to put me off. The main reason was not so much cruelty towards the students as rivalry between the two piano departments, who were both present and couldn’t see eye to eye. We students were caught in the crossfire.

Exams had their own rituals and unwritten rules, mainly revolving around ‘bribing’ teachers, openly and legally, through food, gifts and flowers. All students would arrive with big bouquets of flowers or presents for their teachers. Following the exam there had to be a big feast prepared for the jury members, who would eat, drink alcohol and (presumably) discuss our performances. We students were supposed to supply this feast and prepare it. It was as I was cutting the bread and arranging the bottles of vodka that I heard one of the other students tell me: ‘You are not like other foreign students. You are now one of us’: perhaps the greatest compliment I heard during my six years of trying to fit in.

But it didn’t last long. Following their feast, my teacher eventually approached me. ‘I don’t know how you pulled it off. I didn’t think you could, but somehow you managed to convince them to give you a top mark.’ I was happy, grateful and delighted. But it was a far cry from the joy I had felt on that cold October day when I had been accepted to the Conservatoire. I had been so often reminded that I was undeserving of anything that I had come to believe it. So I could only think: ‘It was lucky. But what now?’

Unlike the jury members, we received no feast, not even a graduation ceremony. It all ended very unceremoniously. A few days later I went to the Dean of foreign students, and the two twin sisters (wonderful people) who assisted him (and I believe are still in post) congratulated me and then pulled a small leather folder from a large pile and wrote my diploma right there in front of me. I soon had to start my farewells and prepare to leave Ukraine for Canada, this time for good. I had to fit six years of my life into two suitcases. I gave most of my stuff to various charities, taking my clothes to an orphanage. Apart from actual orphans, these were children of abusive parents, who had escaped their families. Somehow the glowing smile on the face of a young girl as she saw my shoes fit felt more worthy of celebration than my Conservatoire diploma.

The anxiety of the unknown grew bigger every day. I had worked six years to become ‘one of them’. Now I was leaving, and starting again? From zero? Some of my farewells were unbearably painful; some because I was parting from friends who had grown to be an integral part of my being (actually mainly Michelle’s being), others for different reasons. When I went to bid farewell to my piano teacher, she visibly ignored me for a long time, until I stepped forward and offering the big bouquet of flowers I had brought her. ‘Wasn’t it enough you gave me a candle holder for my grave? Now you want to put flowers on it! Glad I broke the candle holder!’, she shouted back at me in front of a group of teachers and students. She was referring to a present I had brought her from my last trip in Iran, a handcrafted precious decorative item, which at the time she had praised. But that was before her contempt towards me had become overt. I felt my knees shaking. I didn’t know what to say. She walked off, and that was the last I saw of her. Another teacher, a much kinder and more caring one, held my hand and wiped my tears, telling me she couldn’t understand why her colleague was behaving like that. Not even my arrest at the hands of the morality police in Iran had humiliated and destroyed me as much. At once, six years of my life was turned to dust. I was no longer one of them; I was nobody, nothing.

The last evening with Michelle’s friends was like a dream, a midsummer night’s dream. The air was filled with the gentle smell of summer flowers, and a gentle breeze was caressing my cheeks, wet with tears. My two closest friends walked me back, for the last time, to my apartment. ‘We’ll stay in touch’, I said. ‘No, we won’t. We say we will; but time and distance gradually fade things. We must accept it.’ My friend (whom I always called sister) was sharp but true. I hugged each of them: ‘Have a great rest of your life!’

The next morning, the morning of my departure, I opened the door to a smiling Natalia Petrovna, who had come to say goodbye and give me a necklace ‘for good luck, and so that you remember me’. She passed away shortly before the Russian invasion. I still have the necklace and her memory. Then my landlady, Auntie Nela, came with a big bouquet of Lilies (to which I was severely allergic!). She couldn’t help crying: ‘how am I going to survive without you?’. The rent, 170 USD per month, was a fortune for her, as she tried to secure a future for her granddaughter. ‘You had become like my daughter’, she added. I promised her I’d return and see her again. When I finally did, after 12 years, she was no more. Her smile is for ever grafted onto my memory, as she waved me goodbye for the last time.

Between 1997 and 2003, Kyiv changed almost literally in front of my eyes. During this time Kiev became Kyiv, and May Day celebrations (with Lenin placards) gave way to the Europe Day; the 9 May Victory Day became outshone by the 24 August Independence Day. Outside, in the streets, the city had come a long way from the post-Soviet three Macdonald’s as the highest staple of haute cuisine to having boutique teashops where one could choose from most exotic teas. There had been a time when Polish-made imitation Nescafé was an expensive luxury, especially if adding some kind of white creamer, when the best toothpaste brand my mother and I had found was called simply ‘Toothpaste’. Now, night clubs were growing like mushrooms and their opening nights would feed their VIPs caviar and flavoured vodka. But as the surface turned more glittering, so the darker sides of poverty and inequality became more glaringly painful. Part of the grubby authenticity of the city was forever being replaced by what seemed to be just an empty imitation of the West.

***

Kyiv is still a part of me now. It’s where I became Michelle, and then again Assay, and then a self-constructed self; where one became two and then one again (like Tarkovsky’s Domenico). It’s where I learned such pearls of wisdom as: ‘This, too, shall pass’ (the saying is actually from my own country); or ‘in life there are black and white stripes. The only problem is that what you consider black, might have actually been a white stripe’; ‘never talk across the threshold’; ‘spit on your left shoulder if you have to go back where you’ve just left’. It is where I discovered Sterlitz (the hero of a 1970s Soviet spy TV series), where I first truly fell in love with theatre and learned about Meyerhold and Stanislavsky. It is where I appreciated what true friendship is but also that music doesn’t necessarily make people kinder (as many of my music teachers proved).

It is also where I discovered Shostakovich and Skryabin, and where more than once I stared death in the face and laughed it off. It was indeed the best of places, and it was the worst of places. Kyiv was the cradle of my dreams and sorrows.

I close my eyes and can still see so clearly the Sophisky sobor with its golden domes, the kobzar playing bandura in front of the church and singing, the Andriivski Spusk (descent) in the early morning as the market gradually comes alive, the banks of the river Dnipr on hot summer evenings, the chestnut blossoms of Khreshchatyk, the old and now toppled statue of Lenin (the last one) looking nostalgically in the direction of the Besarabska covered market, the enigmatic Pecherskaya Lavra complex of caves, the victory parade on 9 May as I walked alongside my two veteran friends holding a red coronation in anticipation of soldatskaya kasha at the end of Khreshchatyk street, the kashtan (chestnut) flowers turning Kyiv into a beautiful bride ready to get up and dance through the warm fragrant summer nights, and of course the Conservatoire, sitting so proudly on the Independence Square.

Right outside the Conservatoire building, in the corner of the Square, there is the city tower clock, whose chime is the City’s anthem: ‘Yak tebe ne lubity, Kyeve miy?’ (how could I not love you, my Kyiv?) Indeed, how?

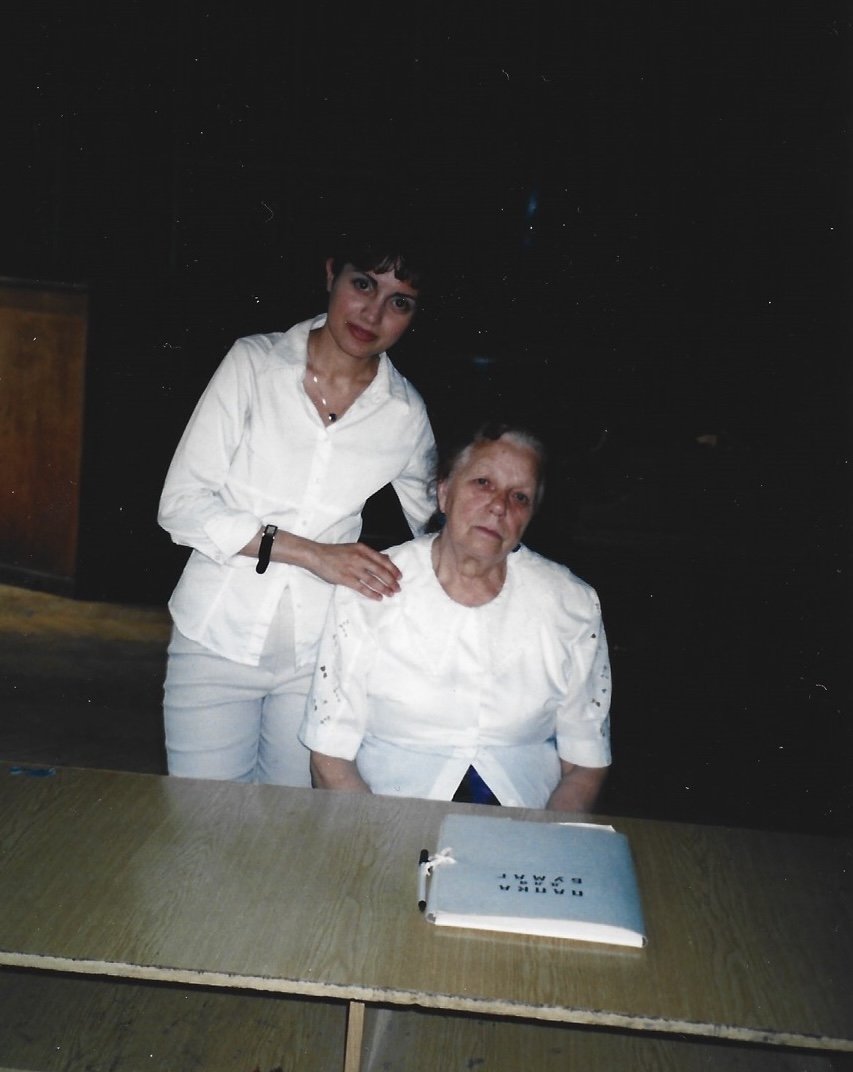

Gallery