Ballet and Dance in Iran

Genres All ContentsThe practice of dance in Iran has its origins in prehistoric eras as far back as at least 5000 BCE. Dancing figures in decorative styles appear on many archaeological artifacts found in different regions of what makes up modern Iran (notably Sialk hill near Kashan and Mushiyan hill in Khusestan)as well as further afield. These artifacts show dancers of both male and female genders, as well as animals and particularly birds. Some of the later images, from the time of the Sassanid era (224 AD – 651 CE) are notable for depicting solo and group female dancers, who often appear naked.

In his 1979 articles for the Persian journal Honar va Mardom, still an invaluable source on the topic, Yahya Zoka refers not only to ceramics and ancient images but also to evidence from the writings of Greek historians such as Herodotus and Xenophon. He also points out the traditions of ancient Persia, in particular Mehrgan celebrations and those associated with worship of Mithra. In his Anabasis, the Greek historian Xenophon refers to a dance as ‘Persian’, describing the movements which suggests its military nature. According to Athenaeus (quoting Duris of Samos), ‘The Persians are taught both horsemanship and dancing; and they believe that the practice of these rhythmical movements strengthens and disciplines the body.’ The same source includes information on the Mithras festival: ‘Only at the festival celebrated by the Persians in honour of Mithra does the Persian king become drunken and dance after the Persian manner.’

By the time of the Sassanid dynasty, the esteem and desire for music and dance had grown substantially, in particular as modes of entertainment for pleasure-loving kings. Apart from figures of female dancers on mosaics and artifacts of this time, there are textual sources referring to the practice of dance. Ferdowsi’s epic Book of Kings, Shahnameh, for instance, describes Bahram Gur’s preoccupation with music and dance. Ferdowsi (10-11 century CE) employs the term ‘Pāy-kub’ [literally foot-stomping] to describe the dancer. The term for dance in Middle-Persian/Pahlavi is more disputed. An invaluable source for not only insights into dance and music but also into the art de la table and even feminine aesthetics, is a Middle Persian/Pahlavi treatise ‘Kusraw Ī Kawādān Ud Rēdak-Ēw (Ḵosrow son of Kavād and the Page)’, in which a boy seeking to serve the King is asked various questions by the latter. In one passage, the boy describes his skills, ending with his mastery of ‘pā-wāzīg’, most likely signifying dance (see Samar Azarnouche). Later in the text, the boy lists various arts as well as wāzīg. This term is translated by most scholars, including Azarnouche, as ‘player’ or ‘joueur’. The list of skills hence most likely refers to games of juggling, acrobacy and animal dressage, rather than to dance as Saloumeh Gholami suggests.

Dance in Islamic Iran

As with music, Islam’s position regarding dance has been complicated, ambiguous and at times self-contradictory. In its strictest from, Islam’s ruling on dance considers it Harām (forbidden). However, ritual ‘dance’ as a means of getting closer to God is practised in some of the branches of Islam, most notably by Sufis. Another Islamic art form that includes both music and ‘dance’ is the practice of Ta’ziyeh (Passion play), representing and commemorating the Shiit martyrdom of Imam Hossein, a grandson of the Prophet Mohammad.

The prohibition of both music and dance seem to stem from interpretations of various types of evidence in the Quran and Hadis. In practice, however, the ambiguity of the position of Islam has meant that, as various historic artifacts and illustrations suggest, dance continued to survive and be practised in the Islamic world, including Iran after its conquest by the Muslim Arabs (633–654)

The increasingly secular Abbassid dynasty (750-1258) saw major developments in the arts. Representations of dance may be found among the surviving architectural and artistic heritages of this period, such as fragments of murals. There is further evidence of the practice of dance from the later period of Islamic Iran, such as the surviving Persian miniature paintings and book illustrations from the Seljuq period (1038-1157) or the illustrations of Ferdowsi’s epic poem Shahnameh (Book of Kings) from the 14th century and beyond. But it was in the Safavid period and coinciding with the development of relationships with foreign powers that Iranian artists started encountering European influences. The 17th-century ‘Celebration of Shah Abbas’, a mural at Chehel-Sotun palace in Isfahan is one of the most celebrated and important surviving artworks depicting group dance practice. The painting also exemplifies Iranian artists’ early awareness of perspective and realism.

The increasingly secular Abbassid dynasty (750-1258) saw major developments in the arts. Representations of dance may be found among the surviving architectural and artistic heritages of this period, such as fragments of murals. There is further evidence of the practice of dance from the later period of Islamic Iran, such as the surviving Persian miniature paintings and book illustrations from the Seljuq period (1038-1157) or the illustrations of Ferdowsi’s epic poem Shahnameh (Book of Kings) from the 14th century and beyond. But it was in the Safavid period and coinciding with the development of relationships with foreign powers that Iranian artists started encountering European influences. The 17th-century ‘Celebration of Shah Abbas’, a mural at Chehel-Sotun palace in Isfahan is one of the most celebrated and important surviving artworks depicting group dance practice. The painting also exemplifies Iranian artists’ early awareness of perspective and realism.

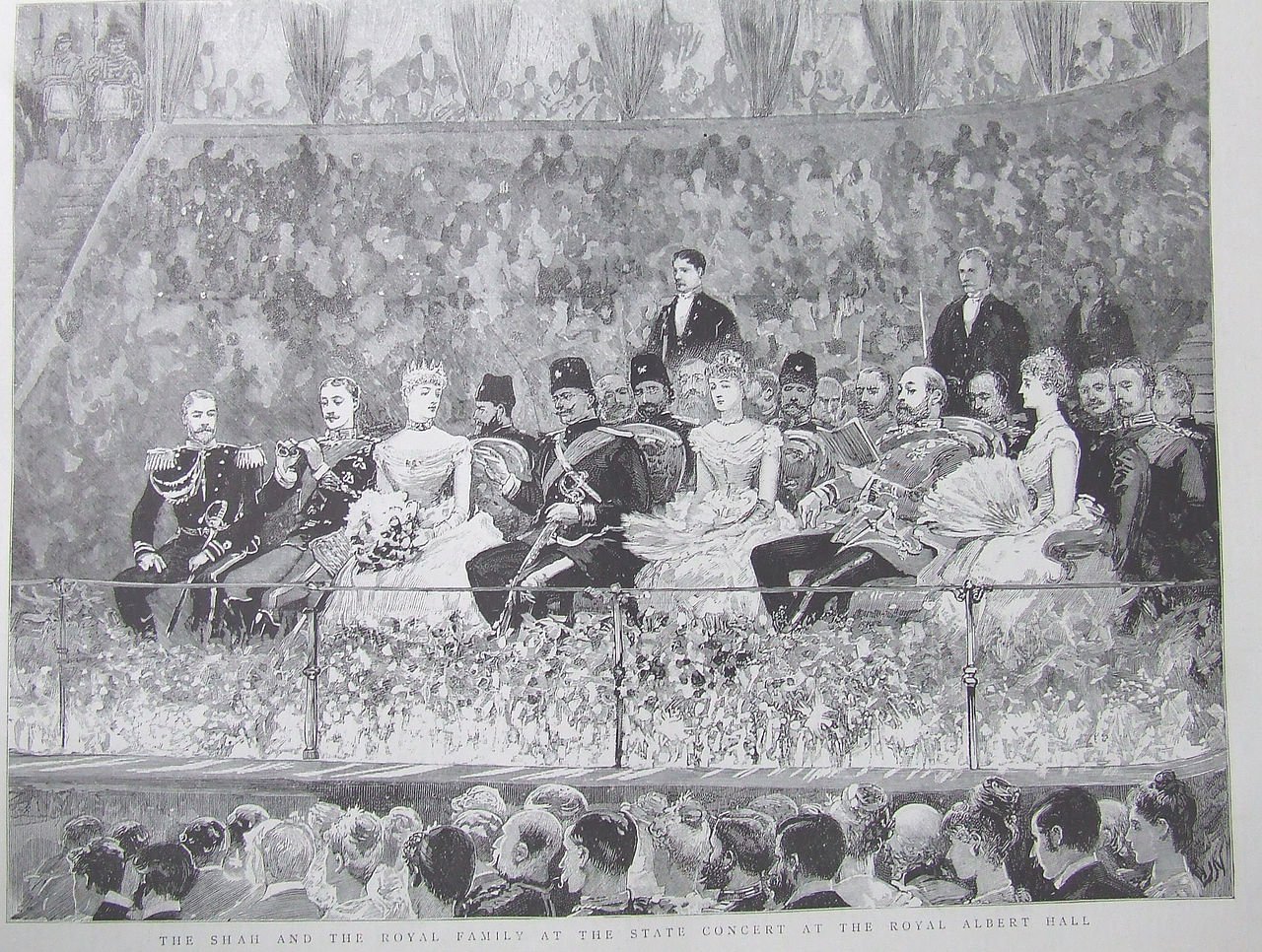

This and other paintings of the Safavid period were used as resources and references by choreographers during the Pahlavi period supposedly to revive and recreate the ‘National’ dance of Iran. Apart from paintings and illustrations, travel diaries of European visitors provide insight into the practice of dance in the Safavid period. In this respect, 1688 Journal de Voyage de Chevalier Chardin en Perse et aux Indes Orientales of the French Jeweller, Sir John Chardin (born Jean-Baptiste Chardin) is of particular importance, especially in its original French version rather than its extensively abridged English translation. This and other travel journals of the time attest to the existence of various groups and categories of dance, as well as details regarding the accompanying music and settings within which dance would take place, for purposes that varied from entertainment to political gestures particularly aimed at foreign dignitaries. The diaries of foreign visitors during the Qajar dynasty (1794-1925) continue to complete the picture of practice of dance, including details on male dancers, itinerant dancers, and information about the Qajar harems and their female dance and music groups (harems were also populated by slaves, including eunuchs, who were mainly from Africa). The dance ensembles were in principle female-only; if they included any male participants, these would be blind or incapacitated from seeing women. The surviving artifacts illustrate female dancers and musicians in attire that would have contrasted with the societal norms of modesty. The paintings (and a few early photos) also attest to the possibility of the influence of Western ballet costumes, thanks to Nasir-e-din Shah’s visits to Europe and his fascination with the western culture.

Dance, Ballet and the Modernisation of Iran

The Pahlavi period saw the most aggressive campaign of modernisation and westernisation of Iran, as set out by the founder of the dynasty, Reza Khan (later Reza Shah). These reforms also saw the most important changes in approach to dance in the country. If until then dance was perceived as an activity associated with hedonism and immorality, during the Pahlavi reign, dance came to be known as an art form per se, and dancers were considered among the most important cultural ambassadors and promoters of the country’s heritage. During this period a new form, ‘National dance’, was developed, which brought national elements and themes into relation with ballet principles. This hybridisation of ballet and Persian dance was generally choreographed by professionally trained masters and standardised the often improvisatory rules of Persian dance. For the purposes of development of this new dance form, folkloric dances were studied by means of field trips by dance research groups.

Following the Qajar-period and Nassir-e-din Shah’s introduction to ballet during his visits to the West, during the Pahlavi reign the dance form was brought to the country by immigrant teachers. A 1935 letter from the Ministry of Education refers to a certain Mr Charles who had established a dance school in Tehran; the letter suggests that officials may have been suspicious of the activities of this foreign resident. By this time, Mme Cornelli, a Russian immigrant married to an Italian, had already set up a dance school in Tehran (1928). This was followed shortly by schools set up by Yelena Aveidisian or Mme Yelena and Sarkis Djanbazian in Tabriz (1933) and Qazvin (1938) respectively. These schools moved to Tehran in 1942 and 1945 respectively. While Djanbazian employed the Vaganova method (a ballet technique and training system devised by the Russian dancer and pedagogue Agrippina Vaganova, which combines the French traditional romantic style with athleticism of Italian style), Cornelli and Avedissian did not use any methodological pedagogy. Another dance school opened in Tehran by Mme Lazarian in 1949. Later some of these dance schools would develop into production companies.

The idea of Iran’s first ballet company took shape in 1944 when Nilla Cram Cook, the then cultural attaché of the American Embassy, decided to form a dance group to revive and preserve the Iranian Performing arts. She later left her work at the Embassy and was hired by the Ministry of Culture. Performances of Cook’s company would mainly take place in the garden of the American Embassy and in the presence of Ashraf (Shah’s sister), royals and dignitaries. In 1946 the group went on its first national tour, then in 1947 on international tours including performances in Turkey, Greece, Italy, and Lebanon. In 1951 Cook’s company set off on their second tour through the Middle East, with repertoire that, apart from performances on Persian themes and poetries, included Arab subjects. The company changed its name to the Ballet of the Lyric Stage of the East, but following the two-year tour the company disbanded in 1953.

The idea of Iran’s first ballet company took shape in 1944 when Nilla Cram Cook, the then cultural attaché of the American Embassy, decided to form a dance group to revive and preserve the Iranian Performing arts. She later left her work at the Embassy and was hired by the Ministry of Culture. Performances of Cook’s company would mainly take place in the garden of the American Embassy and in the presence of Ashraf (Shah’s sister), royals and dignitaries. In 1946 the group went on its first national tour, then in 1947 on international tours including performances in Turkey, Greece, Italy, and Lebanon. In 1951 Cook’s company set off on their second tour through the Middle East, with repertoire that, apart from performances on Persian themes and poetries, included Arab subjects. The company changed its name to the Ballet of the Lyric Stage of the East, but following the two-year tour the company disbanded in 1953.

In 1955, Nejad and Haydeh Ahmadzadeh, the two lead dancers of Cook’s company, were employed by the Department of Fine Arts (affiliated with the Ministry of Culture). Mehrdad Pahlbod, the head of the Department and later the Minister of Culture, assigned Nejad the task of setting up a national ballet school within the premises of Tehran’s Honarestan-e Musighi (Music Conservatoire). William Dollar was invited to be the first ballet master of the National Ballet Academy following its inauguration in September 1956. In 1958 the Academy developed into a classical dance company, which would later come known as the Iranian National Ballet Company.

In the same year, the first official Iranian group of national and folk music and dance was established under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture and Art, under the direction of Nejad Ahmadzadeh. The aim of the group was to revive, restore and promote national folk, music and dances of the country based on material gathered from field trips to remote areas of Iran. The Group performed for many Royals and visiting dignitaries, as well as at dance festivals and tours internationally. The group performed for a week at the Iran Pavillion in Montreal at Expo 67. Apart from the Iranian Group of National and Folk Music, Song and Dance, there was another all-male group from genuine villagers.

Among invited foreign ballet masters and choreographers, Robert de Warren (born 1933) has been credited with playing a crucial role in the development and advancement of the Iranian national and regional dance, directing and staging some of the most important dance projects of the country. He was invited as the ballet master of the Ahmadzadehs’ academy; he and his wife Jacqueline, arrived in 1965 and stayed for 11 years. In 1968 de Warren was invited by Mehrdad Pahlbod, Minister of Culture, to take charge of the National Institute for the Preservation of Folkloric Dance and Music. He made a series of field trips to villages and provinces in Iran, studying local dances and folkloric art.

On 24 February 1970, under the auspices of the Ministry of Culture, the Academy of National and Folkloric Dances of Iran (Honaresta- raqsha-ye meli va mahali-e Iran) was founded. The period of study was set to be at least three years and maximum of five years with a certificate (diploma) at the end. In 1973, painting and music were added, and the name was changed to Art High School (Daneshsara ye Honar). The most talented pupils of this academy were included in de Warren’s performances.

De Warren was responsible for creating the archives and library of teaching and research material. He also established the company of Mahalli Dancers of Iran, who formed part of the Iran National Folklore Organisation founded in 1967, with Parvin Sarlak as artistic director. The purpose of the organisation was to preserve national treasures of Iran in relation to ethnic dances, music and ceremonies. Themes of performances were varied but mainly derived from literature, with occasional references to contemporary issues. De Warren also used artistic and literary themes for classical Iranian dance shows; for instance, in ‘Chehel Sotun’, he used the famous Safavid wall-painting as the premise for recreating the royal party scene of Shah Abbas.

The opening of Rudaki Hall (current Vahdat Hall) in 1967 played an important part in modernisation of the practice of opera and ballet in Iran. The highly sophisticated space offered many opportunities for accommodating the technical requirements of professional standards. It also enabled the collaboration between professional musicians and dancers, allowing live music accompaniment of dance shows.

Political unrest shortened the life of the project of Mahalli Dance as well as many other art forms. Following the 1979 Revolution and the dissolution of all dance activities, many dancers left Iran and/or ended their careers. A few chose to continue as teachers, albeit underground and secretly, at least to start with.

Beyond the borders of the country various initiatives have been made to resurrect the Iranian tradition of dance. One such has been the Nima Kianne-founded Les Ballet Perses, based in Sweden in 2002.

Dance in Iran after the 1979 Revolution

The complex relationship of Islam with music and dance resurfaced shortly after the Revolution, resulting in an initial total absence of all activities, since by the doctrines of the new regime these were deemed pro-Western and corrupt. Dance in particular, due to its connections with the sexually charged cabaret genre suffered a more long-lasting and severe prejudice. Following the Revolution, all dance studios and companies were dissolved and archives reportedly destroyed.

Following the Iran-Iraq war and Khomeini’s death in 1989, there was a gradual slackening of controls, especially gaining momentum under the presidency of the more reformist Khatami (1997-2005). Even before Khatami, artists had started to look for loopholes in ambiguous official rules and regulations. Accordingly dance began a slow resurrection in ways that could eventually be considered compatible with the new ideologies or that would at least evade any hard rules. First and foremost this meant that the words dance and ballet could not be used. These were replaced by what ironically took dance back to its roots – rhythmic movement (Hareket-e mozoon). Farzaneh Kabol and Nader Raghaspur, two of the former dancers of the pre-Revolutionary Mahalli Dance group, were instrumental in establishing this new genre. In Harekat, dancers’ bodies are covered and movements are designed to represent highly spiritual meanings. Performances that included Harekat often include religious and/or literary themes and could be considered theatrical rather than purely ‘dance’ shows.

Another way to circumnavigate controls in music and dance was the phenomenon of female-only performances. This again could be seen as a return to the behind-the-curtain position for women that prevailed in the Qajar period, albeit without the hedonist agendas of the Qajar harems. Female-only performances frequently use major cultural venues such as the Rudaki Hall with the caveat that the entire crew should be female, resulting in practical challenges, especially in technical elements.

Even these new-found limited solutions have been through periods of severe controls as more hardline governments came to power. Such was the period of the Ahmadi-nejad presidency (2005-2013), when even Harekat was highly restricted, as evidenced from a book of rules published by a hardliner youth section, Jalase ye Javanane Ansar al-Hossein-e Mahshad, whereby dance was announced as forbidden except for when in private a woman dances for her husband. Rouhani’s relatively more liberal presidency (2013-2021) again allowed for new ideas and loopholes to emerge, but the term ‘dance’ remained forbidden.

Regardless of the official standing, all official performances (music and dance) have had to go through the labyrinthine process of obtaining permission from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Propaganda. A set of criteria has to be observed and satisfied in order for a performance to receive the coveted permission. The most common reason for cancellation of any event is ‘promotion of corruption, indecency and indecent behaviour’. Even when permitted, it is not unusual for a performance or event to be raided by extremists. Theatre-director, Mahmoud Karimi-Hakkak has poignantly told the story of how his 1999 production of A Midsummer Night Dream with elements of ‘dance’ and music was raided on the first night of its performance:

Another example was the 2003 ‘Amin festival’ at Roudaki Hall, which included folkloric dance and was forced to become a performance for female-only audiences, despite having previously been given to mixed audiences.

Behind closed doors and in secret illegal parties, Iranians have continued to dance, in particular to the tunes of pre-revolutionary popular/variety music, which they have continued to access through illegally smuggled video cassettes, satellite dishes and recently the internet. The 2022 uprisings that followed Mahsa Amini’s arrest and death at the hands of the morality police gave rise to dance as a gesture of dissent and resistance. As the regime forcefully suppressed the uprisings, a new movement emerged in the form of spontaneous dancing which was then videoed and uploaded, albeit briefly and before being censored. These are mainly a combination of Iranian popular dance and Western-inspired hip-hop style movements, but above all they are outlets for silenced voices of a desperate generation that requires freedom in its own country.

Sources (selection)

Samra Azarnouche, Husraw ī Kawādān ud Rēdag-ē. Khosrow Fils De Kawād Et Un Page: texte pehlevi édité et traduit, Paris, Association pour l'Avancement des Études Iraniennes, 2013.

Saloumeh Gholami (ed.), Dance in Iran: Past and Present, Wiesbaden, Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2016. Accompanying videos and media: www.reichart-verlag.de, accessed 13 February 2024.

Ida Meftahi, Gender and Dance in Modern Iran: Biopolitics on Stage, London, Routledge, 2016.

To be completed